On August 16, 2022, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act (the “Act”) into law.[1] The IRS and Treasury are now left to issue guidance on the various provisions of the Act, which has historically been a years-long process. However, a key provision of the Inflation Reduction Act allocates an additional $80 billion to IRS funding which will immediately impact the IRS’s operational and enforcement activities.

$45.6 billion of the IRS funding is earmarked for enforcement activities “to determine and collect owed taxes, to provide legal and litigation support, to conduct criminal investigations, to enforce criminal statutes related to violations of the Internal Revenue laws and other financial crimes, and to hire motor vehicles.”[2] Congress, for its part, expects such enforcement activities along with the additional funding to generate an additional $200 billion in revenue over the next ten years.[3]

Government officials have stressed that low- to upper-middle-income households, defined somewhat arbitrarily as households with less than $400,000 of earnings, and small businesses (undefined) will not see an increase in audit rates. In a letter to IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen directed “that any additional resources—including any new personnel or auditors that are hired—shall not be used to increase the share of small business or households below the $400,000 threshold that are audited relative to historic levels. This means that . . . small business or households earning $400,000 per year or less will not see an increase in the chances they are audited.”[4] Instead, Secretary Yellen directed the IRS to “pursue a robust attack on the tax gap by targeting . . . large corporations, high-net-worth individuals and complex pass-throughs . . . .”[5]

Even with these vague restrictions in place, educated guesses can be made about where the doubled-up enforcement efforts will be focused. This list is by no means exhaustive.[6]

- First, the coordinated all-out attack against “complex pass-throughs” and other perceived tax shelters will continue and intensify; in addition to increasing enforcement against “those who aid and abet” in such transactions.

- Second, enforcement efforts, both criminally and civilly, may further increase against the wealthy.

- Finally, despite reassurances otherwise, enforcement efforts on low- to upper-middle-income households may increase to “historic levels.”

The rationale for enforcement activities in these areas (as well as what such enforcement might look like) is described below.

- Listed Transactions

First, increased funding will occur in the “coordinated campaigns” the IRS has initiated against listed transactions. The IRS is also likely to increase enforcement against so-called “promotors” of listed transactions. Generally, only wealthy taxpayers are able to participate and benefit from these transactions. Therefore, the IRS’s benefit from increasing enforcement in these areas, from a policy perspective, is two-fold: (1) deterring the participation in transactions the IRS has deemed “abusive,” and (2) raising revenue from the wealthy participants.

- Syndicated Conservation Easements

Generally, in order to claim a charitable contribution deduction, one must donate their entire interest in the donated property. For instance, if you donate cash or stock to a charitable organization you cannot withhold the right to use that property at a later date—incomplete gifts are not permitted. The exception to this general rule is found in I.R.C. section 170(h), which allows landowners to donate a qualified real property interest (i.e., a conservation easement) and still take a charitable contribution deduction.[7] The donation is only of the easement, so the landowner retains ownership of the real property, but the property is now subject to a perpetual (forever) easement. The value of the deduction is generally equal to the difference between the value of the property before the easement minus the value of the property after the easement. For example, farmland that could be developed is generally more valuable than farmland subject to a conservation easement that can never be developed—that difference in value is the amount of the charitable deduction.

The IRS described certain easement transactions involving partnerships in Listing Notice 2017-10 and deemed such transactions “abusive.” Notice 2017-10 transactions occur when so-called “syndicators” market and sell interests in property-owning pass-through entities to investors seeking tax benefits. Generally, to fall under Notice 2017-10 an investor must receive a charitable contribution deduction that equals or exceeds two and one-half times the investor’s investment.

After the transaction was “listed” in December of 2016 in Notice 2017-10, examinations of such transactions became more and more common. On November 12, 2019, Commissioner Rettig stated that “[p]utting an end to these abusive schemes is a high priority for the IRS.”[8] The IRS’s continued commitment to enforcement in this area is a strong indicator that these efforts will receive portions of the funds earmarked in the Inflation Reduction Act.

- Micro captives

A micro-captive is a type of captive insurance company taxed under I.R.C. section 831(b). A section 831(b) company is only taxed on its “taxable investment income” and not taxed on its underwriting (or insurance) income; conversely, an underwriting loss is not deductible against its “taxable investment income.” Thus, net underwriting profits are not taxed until withdrawn. In order to make a section 831(b) election, the company’s written premiums must not exceed a certain threshold, which for 2022 is $2.45 million.

In 2016, the IRS issued Notice 2016-66, which stated that section 831(b) captive insurance programs have “a potential for tax avoidance or evasion.” But, the IRS qualified that it and the Treasury Department “lack sufficient information to identify which § 831(b) arrangements should be identified specifically as a tax avoidance transaction and may lack sufficient information to define the characteristics that distinguish the tax avoidance transactions from other § 831(b) related-party transactions.” The Notice also affirmatively put taxpayers who participated in such transactions on notice that their involvement in such programs could subject them to penalties, and imposed disclosure requirements on those taxpayers.

Since issuing Notice 2016-66, the IRS has aggressively focused on auditing section 831(b) companies and challenging such arrangements in the Tax Court and beyond. The IRS is currently on a “winning streak” for the cases it has taken to trial, and over the last few years have dramatically ramped up its efforts to target section 831(b) companies. In 2020, the IRS announced that it was establishing 12 new audit teams “expected to open audits related to thousands of [section 831(b)] taxpayers” and stated that “[e]nforcement activity in this area is being significantly increased.”[9]

As with conservation easements, it can be anticipated that the IRS will use resources from the Inflation Reduction Act to continue its campaign against section 831(b) insurance companies.

- Targeting “Promotors” and Advisors

I.R.C. sections 6694, 6700, and 6701 permit the IRS to assess penalties against return preparers, promotors, and those who prepare documents used for tax reporting (such as appraisers), respectively, when certain criteria are met.

Increased funding for enforcement in this area is also likely because on April 19, 2021, the IRS announced the establishment of the IRS Office of Promotor Investigations (OPI), which was an extension of the efforts of the Promoter Investigations Coordinator that began in the summer of 2020.[10] The OPI was established to continue the “increased focus on promotors of abusive tax avoidance transactions” and “coordinate efforts across multiple business divisions to address abusive syndicated conservation easement and abusive micro-captive insurance arrangements, as well as other transactions.”[11]

- The High Hanging Fruit

Yellen’s comments make clear that the wealthy are going to be a central enforcement focus. Additionally, the IRS has several specific enforcement programs already in place which can expect to see increased funding and activity.

For instance, on February 19, 2020, the IRS announced that it would increase efforts to “visit” high-income taxpayers who have failed to timely file their tax returns.[12] At that time, the IRS “shifted a considerable amount of resources” towards addressing so-called high income non-filers (“HINFs”).[13]

The IRS identifies HINFs through its whistleblower program; information received from the United States Attorney offices; investigations by other law enforcement agencies; tips from colleagues, neighbors, and friends; and information obtained through tax treaties with foreign countries.[14] The IRS has also increased efforts to use data mining and cyber analytics to identify such individuals, such as for cryptocurrency transactions, and to more efficiently use information reported on Forms such as 1099s. Each of these programs is likely to see greatly increased funding.

The IRS is also likely to increase scrutiny of foreign bank account reporting (“FBAR”) for citizens with overseas financial assets. The Bank Secrecy Act of 1970, 31 U.S.C. § 5311 et seq. requires US persons with more than $10,000 (in the aggregate) held in bank accounts, brokerage accounts, and mutual funds in a foreign country to file an FBAR with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”), or risk penalties of at least $10,000.[15] Pending the results of Bittner v. United States, this $10,000 penalty may apply to each taxpayer per year, or may be applicable to each unreported account per year.[16]

For certain HINFs, there may be options to come into compliance and negate criminal prosecution, certain penalties, or further action by the IRS. Speaking with a qualified tax attorney at the earliest possible opportunity is critical to taking advantage of these programs.

In addition to targeting HINFs, the IRS is likely to continue its scrutiny of reporting transactions involving cryptocurrencies. The IRS added cryptocurrency transactions to its Voluntary Disclosure Program on February 15, 2022, after increased scrutiny in that area.[17] Adding transactions in virtual currency, such as the receipt, sale, exchange, or other disposition of financial interests in cryptocurrency, to the Voluntary Disclosure Program was a signal to taxpayers that increased scrutiny, including criminal prosecution, is likely. Eligibility to participate in the Voluntary Disclosure Program evaporates once a taxpayer is either audited or investigated by the IRS. With additional funding, taxpayers will want to consider with their tax professional whether their transactions have been reported correctly and consider, if appropriate, such programs.

- Low to Upper-Middle Income Households.

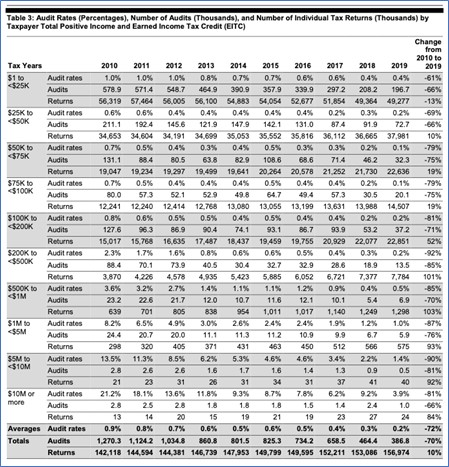

Finally, Yellen’s restriction does not prevent an increase in audits on households earning less than $400,000 per year. Rather, the restriction prevents increasing audit rates beyond “historic levels” for those households. However, such audits are currently at historic lows. In fact, the audit rates for households earning less than $500,000 per year have decreased dramatically between 2010 and 2019, with audits decreasing between 61% and 92% depending on income level. While it is unclear what timeframe may be encompassed by the phrase “historic,” a recent May 2022 GAO report tracks audit rates back to 2010, as follows:

U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-22-104960, Tax Compliance: Trends of IRS Audit Rates and Results for Individual Taxpayers by Income (2022).

Similar government data relating to 2020 and 2021 is not yet available, although we do know that after a dip in examinations in 2020 (likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic), the total number[18] of returns examined returned to slightly less than the number examined in 2019.[19] Nevertheless, looking back for a period of even 5 years could result in audit rates on households earning less than $400,000 increasing substantially (compare the GAO table’s 2019 “Audit Rates” to the 2016 “Audit Rates”). In 2017, in most income brackets, the “historic levels” of audit rates are double (or more) than what they were in 2019.[20]

Audits at lower-income levels result in more bang for the IRS’s buck. “Audits of the lowest-income taxpayers, particularly those claiming the EITC, resulted in higher amounts of recommended additional tax per audit hour compared to all income groups except for the highest-income taxpayers.”[21] If the IRS can, it almost certainly will justify increasing audits on these individuals from current levels to “historic levels” because the return is higher on low-hanging fruit.

[1] Inflation Reduction Act, H.R. 5376, 117th Cong. (2021-2022).

[2] IRS Budget and Workforce: Table 30. Costs incurred by Budget Activity, Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021, IRS, https://www.irs.gov/statistics/irs-budget-and-workforce (last updated May 26, 2022).

[3] Phill Swagel, Effects of Increased Funding for the IRS, Congressional Budget Off.: CBO Blog (Sept. 2, 2021) https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57444; see also Congressional Budget Off., Estimated Budgetary Effects of H.R. 5376, The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 at 3, 14, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-08/hr5376_IR_Act_8-3-22.pdf (revised Aug. 5, 2022).

[4] Letter from Janet L. Yellen, Secretary of the Treasury, Department of the Treasury to Charles P. Rettig, Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service (Aug. 10, 2022).

[5] Id.

[6] A more comprehensive (but no less complete) list of areas likely to see increased funding can be found at Large Business and International Active Campaigns, IRS, https://www.irs.gov/businesses/corporations/lbi-active-campaigns (last updated Aug. 17, 2022), which comprises some 54 areas a single division of the IRS has characterized as “Active Campaigns.”

[7] The rules under Sections 170(h)(1) through (5) and Treas. Reg. section 1.170A-14 are highly complex and not the focus of this article. This sentence is meant to be illustrative and not instructive.

[8] I.R.S. News Release IR-2019-182 (Nov. 12, 2019).

[9] I.R.S. News Release IR-2020-26 (Jan. 31, 2020).

[10] I.R.S. News Release IR-2021-88 (Apr. 19, 2021).

[11] I.R.S. News Release IR-2021-88 (Apr. 19, 2021).

[12] I.R.S. News Release IR-2020-34 (Feb. 19, 2020).

[13] Eric Hylton, How the IRS prioritizes compliance work on high income non-filers through national and international efforts, IRS: A Closer Look (Dec. 3. 2020), https://www.irs.gov/about-irs/how-the-irs-prioritizes-compliance-work-on-high-income-non-filers-through-national-and-international-efforts.

[14] Id.

[15] Understand how to report foreign bank and financial accounts, IRS, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/understand-how-to-report-foreign-bank-and-financial-accounts (Apr. 2019).

[16] No. 21-1195, 2022 WL 2203345, at *1 (U.S. June 21, 2022) (certiorari granted).

[17] I.R.S. News Release IR-2020-34 (Feb. 15, 2020); see also Cryptocurrency added to IRS Voluntary Disclosure Program – the good, the bad, and the basics, Dentons Insights, (March 11, 2019) https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/alerts/2022/march/11/cryptocurrency-added-to-irs-voluntary-disclosure-program–the-good-the-bad-and-the-basics.

[18] The total number of returns examined includes households earning more than $400,000 annually.

[19] Internal Revenue Service Data Book 2021 at p. 35, available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p55b.pdf.

[20] U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-22-104960, Tax Compliance: Trends of IRS Audit Rates and Results for Individual Taxpayers by Income (2022).

[21] U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-22-104960, Tax Compliance: Trends of IRS Audit Rates and Results for Individual Taxpayers by Income (2022).